R. A. B. Mynors on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Roger Aubrey Baskerville Mynors (28 July 190317 October 1989) was an English

In 1922, Mynors won the Domus

In 1922, Mynors won the Domus

In 1944, encouraged by Fraenkel, Mynors took up an offer to assume the Kennedy Professorship of Latin at the

In 1944, encouraged by Fraenkel, Mynors took up an offer to assume the Kennedy Professorship of Latin at the

classicist

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

and medievalist

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , ''asteriskos'', "little star", is a typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a heraldic star.

Computer scientists and mathematicians often vo ...

who held the senior chairs of Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

at the universities of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

and Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

. A textual critic

Textual criticism is a branch of textual scholarship, philology, and of literary criticism that is concerned with the identification of textual variants, or different versions, of either manuscripts or of printed books. Such texts may range in da ...

, he was an expert in the study of manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printing, printed or repr ...

s and their role in the reconstruction of classical texts.

Mynors's career spanned most of the 20th century and straddled two of England's leading universities, Oxford and Cambridge. Educated at Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, C ...

, he read Literae Humaniores at Balliol College, Oxford

Balliol College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. One of Oxford's oldest colleges, it was founded around 1263 by John I de Balliol, a landowner from Barnard Castle in County Durham, who provided the f ...

, and spent the early years of his career as a Fellow of that college. He was Kennedy Professor of Latin at Cambridge from 1944 to 1953 and Corpus Christi Professor of Latin

The Corpus Christi Professorship of the Latin Language and Literature, also known simply as the Corpus Christi Professorship of Latin and previously as the Corpus Professorship of Latin, is a chair in Latin literature at Corpus Christi College, U ...

at Oxford from 1953 until his retirement in 1970. He died in a car accident in 1989, aged 86, while travelling to his country residence, Treago Castle

Treago Castle is a fortified manor house in the parish of St Weonards, Herefordshire, England (). Built c. 1500, it was recorded as a Grade I listed building on 30 April 1986—based on its extant medieval architecture, quadrangle courtyard l ...

in Herefordshire

Herefordshire () is a county in the West Midlands of England, governed by Herefordshire Council. It is bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh counties of Monmouthshire ...

.

Mynors's reputation is that of one of Britain's foremost classicists. He was an expert on palaeography

Palaeography (American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, UK) or paleography (American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, US; ultimately from grc-gre, , ''palaiós'', "old", and , ''gráphein'', "to write") ...

, and has been credited with unravelling a number of highly complex manuscript relationships in his catalogues of the Balliol and Durham Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of Christ, Blessed Mary the Virgin and St Cuthbert of Durham, commonly known as Durham Cathedral and home of the Shrine of St Cuthbert, is a cathedral in the city of Durham, County Durham, England. It is the seat of t ...

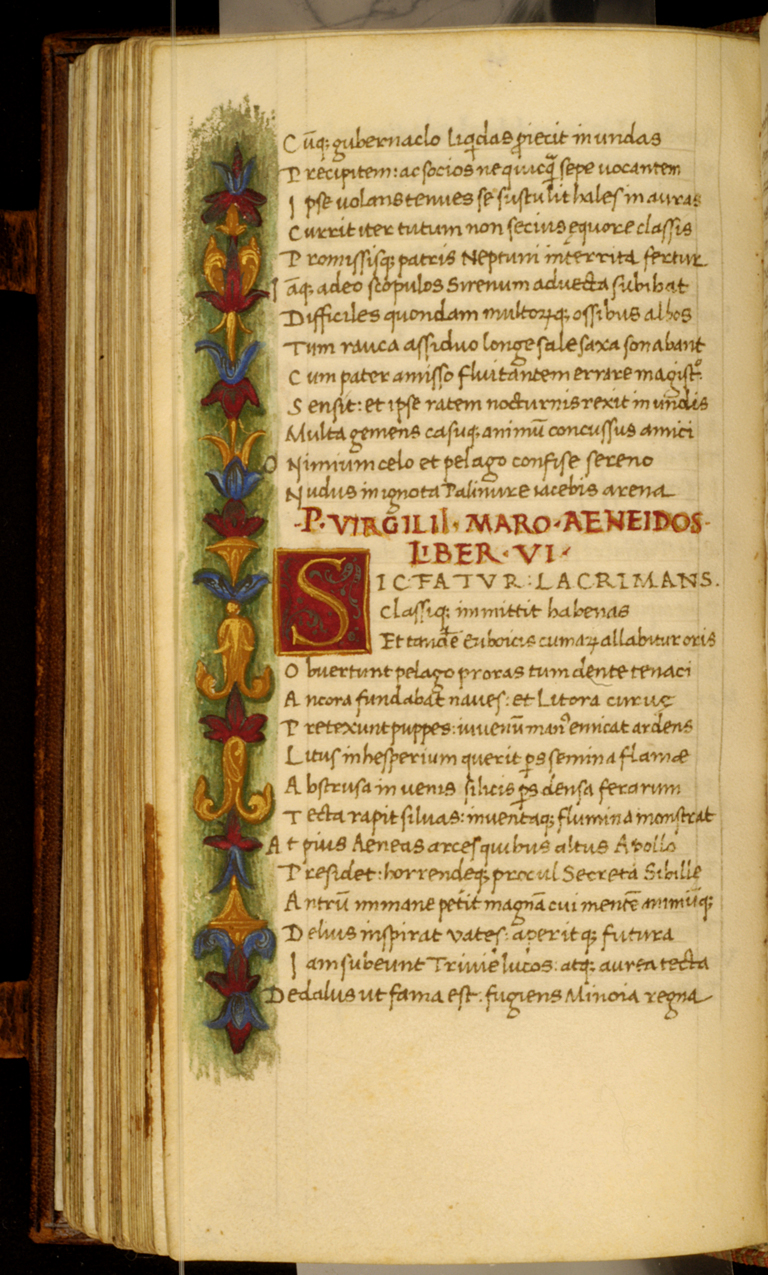

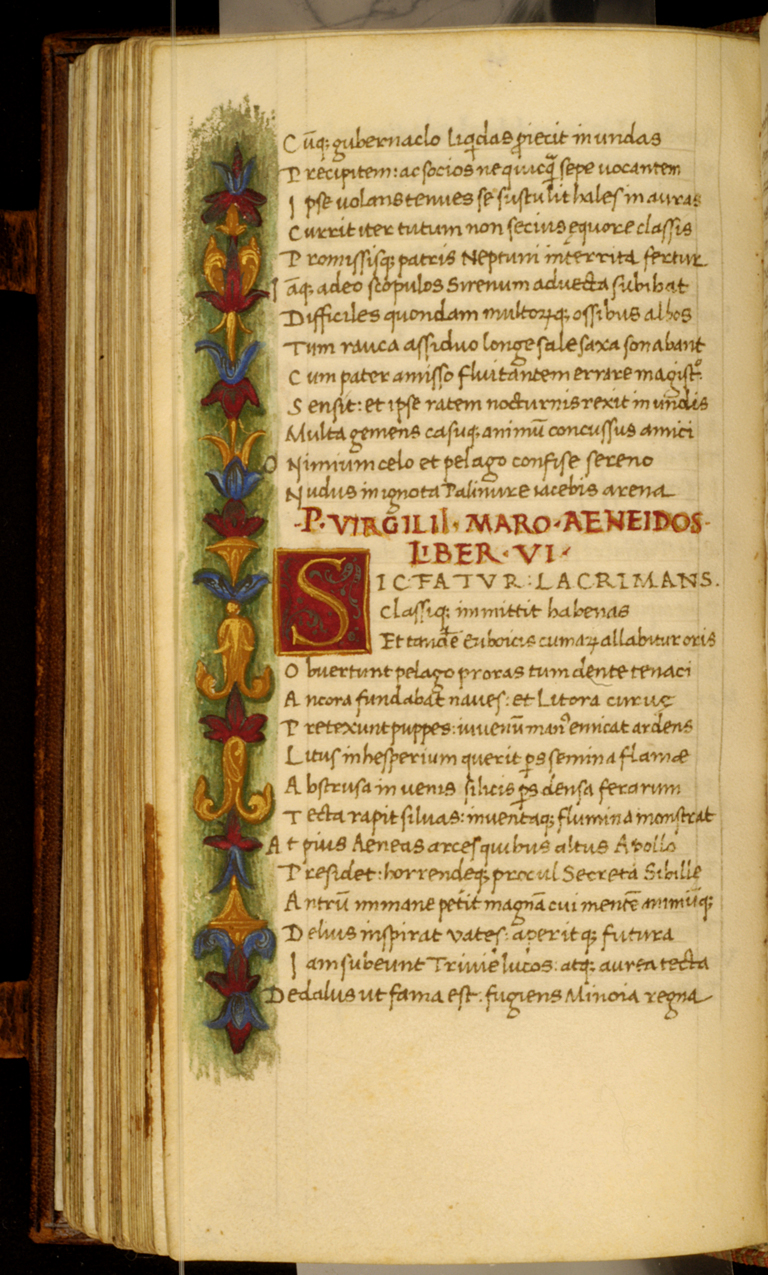

libraries. His publications on classical subjects include critical editions of Vergil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

, Catullus

Gaius Valerius Catullus (; 84 - 54 BCE), often referred to simply as Catullus (, ), was a Latin poet of the late Roman Republic who wrote chiefly in the neoteric style of poetry, focusing on personal life rather than classical heroes. His s ...

, and Pliny the Younger. The final achievement of his scholarly career, a comprehensive commentary on Vergil's ''Georgics

The ''Georgics'' ( ; ) is a poem by Latin poet Virgil, likely published in 29 BCE. As the name suggests (from the Greek word , ''geōrgika'', i.e. "agricultural (things)") the subject of the poem is agriculture; but far from being an example ...

'', was published posthumously. In addition to honorary degrees and fellowships from various institutions, Mynors was created Knight Bachelor

The title of Knight Bachelor is the basic rank granted to a man who has been knighted by the monarch but not inducted as a member of one of the organised orders of chivalry; it is a part of the British honours system. Knights Bachelor are the ...

in 1963.

Early life and secondary education

Roger Aubrey Baskerville Mynors was born inLangley Burrell

Langley Burrell is a village just north of Chippenham, Wiltshire, England. It is the largest settlement in the civil parish of Langley Burrell Without which includes the hamlets of Peckingell (south of the village) and Kellaways (to the east on ...

, Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

, into a family of Herefordshire

Herefordshire () is a county in the West Midlands of England, governed by Herefordshire Council. It is bordered by Shropshire to the north, Worcestershire to the east, Gloucestershire to the south-east, and the Welsh counties of Monmouthshire ...

gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

. The Mynors family had owned the estate of Treago Castle

Treago Castle is a fortified manor house in the parish of St Weonards, Herefordshire, England (). Built c. 1500, it was recorded as a Grade I listed building on 30 April 1986—based on its extant medieval architecture, quadrangle courtyard l ...

since the 15th century, and he resided there in later life. His mother was Margery Musgrave, and his father, Aubrey Baskerville Mynors, was an Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

clergyman and rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of Langley Burrell, who had been secretary to the Pan-Anglican Congress The first Pan-Anglican Congress was held in London (United Kingdom) from June 15 to June 24, 1908, immediately prior to the Fifth Lambeth Conference held in July of the same year. Designed as a consultation on mission, the Congress was a meeting of ...

, held in London in 1908. Among his four siblings was his identical twin brother Humphrey Mynors, who went on to become Deputy Governor of the Bank of England A Deputy Governor of the Bank of England is the holder of one of a small number of senior positions at the Bank of England, reporting directly to the Governor.

According to the original charter of 27 July 1694 the Bank's affairs would be supervise ...

. The brothers shared a close friendship and lived together in their ancestral home after Roger's retirement.

Mynors attended Summer Fields School

Summer Fields is a fee-paying boys' independent day and boarding preparatory school in Summertown, Oxford. It was originally called Summerfield and used to have a subsidiary school, Summerfields, St Leonards-on-Sea (known as "Summers mi").

H ...

in Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, and in 1916 entered Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, C ...

as a King's Scholar

A King's Scholar is a foundation scholar (elected on the basis of good academic performance and usually qualifying for reduced fees) of one of certain public schools. These include Eton College; The King's School, Canterbury; The King's School ...

. At Eton, he was part of a generation of pupils that included the historian Steven Runciman

Sir James Cochran Stevenson Runciman ( – ), known as Steven Runciman, was an English historian best known for his three-volume ''A History of the Crusades'' (1951–54).

He was a strong admirer of the Byzantine Empire. His history's negative ...

and the author George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalitar ...

. His precocious interest in Latin literature

Latin literature includes the essays, histories, poems, plays, and other writings written in the Latin language. The beginning of formal Latin literature dates to 240 BC, when the first stage play in Latin was performed in Rome. Latin literature ...

and its transmission was fostered by the encouragement of two of his teachers, Cyril Alington

Cyril Argentine Alington (22 October 1872 – 16 May 1955) was an English educationalist, scholar, cleric, and author. He was successively the headmaster of Shrewsbury School and Eton College. He also served as chaplain to King George V and as De ...

and M. R. James

Montague Rhodes James (1 August 1862 – 12 June 1936) was an English author, medievalist scholar and provost of King's College, Cambridge (1905–1918), and of Eton College (1918–1936). He was Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambrid ...

. Alington became an influential mentor and friend since he, like Mynors, was fascinated with the manuscript traditions of medieval Europe

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

.

Academic career

Balliol College, Oxford

In 1922, Mynors won the Domus

In 1922, Mynors won the Domus exhibition

An exhibition, in the most general sense, is an organized presentation and display of a selection of items. In practice, exhibitions usually occur within a cultural or educational setting such as a museum, art gallery, park, library, exhibition ...

, a scholarship to study Classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

at Balliol College, Oxford

Balliol College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. One of Oxford's oldest colleges, it was founded around 1263 by John I de Balliol, a landowner from Barnard Castle in County Durham, who provided the f ...

. Attending the college at the same time as the literary critic Cyril Connolly

Cyril Vernon Connolly CBE (10 September 1903 – 26 November 1974) was an English literary critic and writer. He was the editor of the influential literary magazine '' Horizon'' (1940–49) and wrote '' Enemies of Promise'' (1938), which comb ...

, the musicologist Jack Westrup

Sir Jack Westrup (26 July 190421 April 1975) was an English Musicology, musicologist, writer, teacher and occasional conductor and composer.

Biography

Jack Allan Westrup was the second of the three sons of George Westrup, insurance clerk, of Dulw ...

, the future Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford

The Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford is the chief executive and leader of the University of Oxford. The following people have been vice-chancellors of the University of Oxford (formally known as The Right Worshipful the Vice-Chancel ...

, Walter Fraser Oakeshott

Sir Walter Fraser Oakeshott (11 November 1903 – 13 October 1987) was a schoolmaster and academic, who was Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford. He is best known for discovering the Winchester Manuscript of Sir Thomas Malory's ''Le Mort ...

, and the historian Richard Pares

Richard Pares (25 August 1902 – 3 May 1958) was a British historian. He "was considered to be among the outstanding British historians of his time."

Family life and education

The eldest son of the five children of the historian Bernard Pares ...

, he was highly successful in his academic studies. Graduating with a Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four years ...

in 1926, he won the Hertford (1924), Craven (1924), and Derby (1926) scholarships. He was elected to a fellow

A fellow is a concept whose exact meaning depends on context.

In learned or professional societies, it refers to a privileged member who is specially elected in recognition of their work and achievements.

Within the context of higher education ...

ship at Balliol and became a tutor in Classics. In 1935 he was elevated to a University Lecturership. At the time of his appointment, much of Mynors's teaching focused on the poet Vergil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

, whose complete works he edited in the following decades.

His tenure at Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

saw the beginning of his comprehensive work on medieval manuscripts. From the late 1920s onwards, Mynors was drawn more to matters of codicology than to purely classical questions. He prepared an edition of the 6th-century scholar Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Roman statesman, renowned scholar of antiquity, and writer serving in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senator'' w ...

, for which he travelled extensively in continental Europe; a critical edition was published in 1937. In 1929, he was appointed librarian

A librarian is a person who works professionally in a library providing access to information, and sometimes social or technical programming, or instruction on information literacy to users.

The role of the librarian has changed much over time, ...

of Balliol College. This position gave impetus to create a catalogue of the college's medieval manuscripts. A similar project, a catalogue of the manuscripts housed at Durham Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of Christ, Blessed Mary the Virgin and St Cuthbert of Durham, commonly known as Durham Cathedral and home of the Shrine of St Cuthbert, is a cathedral in the city of Durham, County Durham, England. It is the seat of t ...

, was compiled in the 1930s. Mynors's interest in codicology gave rise to a close co-operation with the medievalists Richard William Hunt

Richard William Hunt (11 April 1908 – 13 November 1979) was a scholar, grammarian, palaeographer, editor, and author of a number of books about medieval history. He began his career as a lecturer in palaeography at Liverpool University, and ...

and Neil Ripley Ker.

In 1936, towards the end of his tenure at Balliol, Mynors met Eduard Fraenkel

Eduard David Mortier Fraenkel FBA () was a German classical scholar who served as the Corpus Christi Professor of Latin at the University of Oxford from 1935 until 1953. Born to a family of assimilated Jews in the German Empire, he studied C ...

, then holder of a chair in Latin at Oxford. Having relocated to England because of the increasing discrimination against German Jews, Fraenkel was a leading exponent of Germany's scholarly tradition. His mentorship contributed to Mynors's transformation from amateur scholar to a professional critic of Latin texts. They maintained a close friendship, which exposed Mynors to other German philologists, including Rudolf Pfeiffer

Rudolf Carl Franz Otto Pfeiffer (20 September 1889 – 5 May 1979) was a German classical philologist. He is known today primarily for his landmark, two-volume edition of Callimachus and the two volumes of his ''History of Classical Scholarsh ...

and Otto Skutsch

Otto Skutsch (6 December 1906 – 8 December 1990) was a German-born British classicist and academic, specialising in classical philosophy. He was Professor of Latin at University College London from 1951 to 1972.

Early life

Skutsch was born on ...

.

Mynors spent the winter of 1938 as a visiting scholar at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

. In 1940, after a brief return to Balliol, British involvement in the Second World War led to his being employed at the Exchange Control Department of Her Majesty's Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury), occasionally referred to as the Exchequer, or more informally the Treasury, is a department of His Majesty's Government responsible for developing and executing the government's public finance policy and e ...

responsible for the administration of foreign currency transactions. At Balliol, Mynors taught from 1926 until 1944, a time during which he mentored a number of future scholars, including the Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein ( ; ; 26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrians, Austrian-British people, British philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy o ...

expert David Pears

__NOTOC__

David Francis Pears, FBA (8 August 1921 – 1 July 2009) was a British philosopher renowned for his work on Ludwig Wittgenstein.

An Old Boy of Westminster School,David Pears: philosopher'' (obituary) ''The Times,'' 3 July 2009, Archiv ...

and the classicist Donald Russell.

Pembroke College, Cambridge

In 1944, encouraged by Fraenkel, Mynors took up an offer to assume the Kennedy Professorship of Latin at the

In 1944, encouraged by Fraenkel, Mynors took up an offer to assume the Kennedy Professorship of Latin at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

. He also became a fellow of Pembroke College. In 1945, shortly after moving to Cambridge, he married Lavinia Alington, a medical researcher and daughter of his former teacher and Eton headmaster, Cyril Alington. The couple had no children. The move to Cambridge meant an advancement of his academic career, but he soon came to contemplate a return to Oxford. He applied unsuccessfully to become master of Balliol College after the position had been vacated by Sandie Lindsay in 1949. The historian David Keir

David Keir (1884–1971) was a British film actor, who also appeared on stage

Stage or stages may refer to:

Acting

* Stage (theatre), a space for the performance of theatrical productions

* Theatre, a branch of the performing arts, often ref ...

was elected in his stead.

His post at Cambridge caused changes to Mynors's profile as an academic. His duties at Balliol had centred on the supervision of undergraduates, while he was free to focus on palaeographical

Palaeography ( UK) or paleography ( US; ultimately from grc-gre, , ''palaiós'', "old", and , ''gráphein'', "to write") is the study of historic writing systems and the deciphering and dating of historical manuscripts, including the analysi ...

topics in his research. At Cambridge, Mynors was required to lecture extensively on Latin literature and to supervise research students, a task of which he had little experience. The duties of his university post left little time to get involved in the activities of the college, which led Mynors to regret his departure from Oxford, going so far as to describe the decision as a "fundamental error" in a personal letter.

Although his post was chiefly that of a Latinist, his involvement in the publication of medieval texts intensified during the 1940s. After he was approached by V. H. Galbraith

Vivian Hunter Galbraith (15 December 1889 – 25 November 1976) was an English historian, fellow of the British Academy and Oxford Regius Professor of Modern History.

Early career

Galbraith was born in Sheffield, son of David Galbraith, ...

, a historian of the Middle Ages, Mynors became an editor on Nelson's ''Medieval Texts'' series in 1946. Working on the series first as a joint editor, and from 1962 as an advisory editor, he edited the Latin text for a number of volumes. He was the principal author of editions of Walter Map

Walter Map ( la, Gualterius Mappus; 1130 – 1210) was a medieval writer. He wrote '' De nugis curialium'', which takes the form of a series of anecdotes of people and places, offering insights on the history of his time.

Map was a court ...

's ''De nugis curialium

''De nugis curialium'' (Medieval Latin for ''"Of the trifles of courtiers"'' or loosely ''"Trinkets for the Court"'') is the major surviving work of the 12th century Latin author Walter Map. He was an English courtier of Welsh descent. Map claimed ...

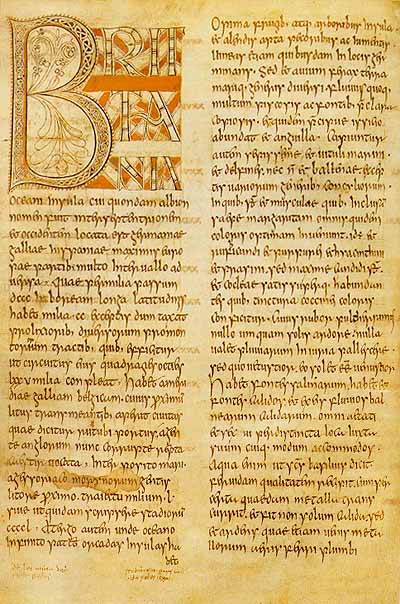

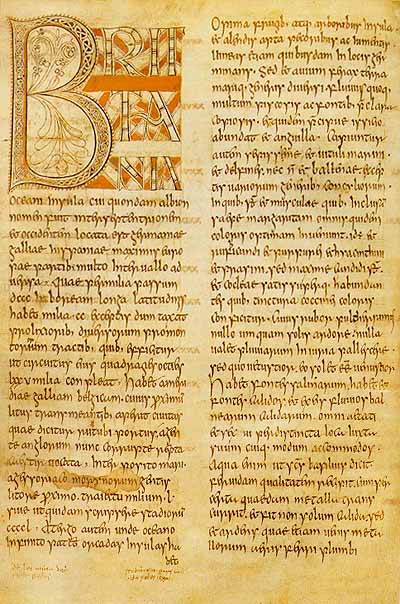

'' and of Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom o ...

's ''Ecclesiastical History

__NOTOC__

Church history or ecclesiastical history as an academic discipline studies the history of Christianity and the way the Christian Church has developed since its inception.

Henry Melvill Gwatkin defined church history as "the spiritual ...

''. In 1947, he collaborated with the Oxford historian Alfred Brotherston Emden

Alfred Brotherston Emden (1888–1979) was an Oxford University historian and Principal of St Edmund Hall from 1929 to 1951. He published widely on matters concerning St Edmund Hall and the medieval church. His generous gifts, and lifelong asso ...

, who consulted Mynors for his own work on the history of the University of Oxford while assisting, in turn, with the Balliol catalogue.

Corpus Christi College, Oxford

In 1953, Mynors was appointedCorpus Christi Professor of Latin

The Corpus Christi Professorship of the Latin Language and Literature, also known simply as the Corpus Christi Professorship of Latin and previously as the Corpus Professorship of Latin, is a chair in Latin literature at Corpus Christi College, U ...

and could thus return to Oxford to succeed Eduard Fraenkel. At the time, there was no precedent for such a move between senior chairs at Oxford and Cambridge. Most of his work as an editor of Latin texts took place during this second period at Oxford. Working for the ''Oxford Classical Texts

Oxford Classical Texts (OCT), or Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis, is a series of books published by Oxford University Press. It contains texts of ancient Greek and Latin literature, such as Homer's ''Odyssey'' and Virgil's ''Aeneid'', ...

'' series, he produced critical editions of the complete works of Catullus

Gaius Valerius Catullus (; 84 - 54 BCE), often referred to simply as Catullus (, ), was a Latin poet of the late Roman Republic who wrote chiefly in the neoteric style of poetry, focusing on personal life rather than classical heroes. His s ...

(1958) and Vergil (1969), and of Pliny the Younger's '' Epistulae'' (1963). Though focusing on classical subjects, he continued to work on manuscripts as a curator at the Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. It derives its name from its founder, Sir Thomas Bodley. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second- ...

. In the 17 years he spent at the college, Mynors sought to maintain its position as a centre of excellence in the Classics and fostered contacts with a new generation of Latinists, including E. J. Kenney

Edward John Kenney, (29 February 1924 – 23 December 2019), usually known as E. J. Kenney, was a British Latinist who served as the Kennedy Professor of Latin until his retirement in 1984. Specialising in transmission and textual criticism, h ...

, Wendell Clausen, Leighton Durham Reynolds

Leighton Durham Reynolds () was a British Latinist who was known for his work on textual criticism. Spending his entire teaching career at Brasenose College, Oxford, he prepared the most commonly cited edition of Seneca the Younger's ''Letter ...

, R. J. Tarrant and Michael Winterbottom

Michael Winterbottom (born 29 March 1961) is an English film director. He began his career working in British television before moving into features. Three of his films—''Welcome to Sarajevo'', ''Wonderland'' and ''24 Hour Party People''—h ...

.

Retirement and death

In 1970, Mynors retired from his teaching duties and relocated to his estate at Treago Castle. In addition to an intense dedication toarboriculture

Arboriculture () is the cultivation, management, and study of individual trees, shrubs, vines, and other perennial woody plants. The science of arboriculture studies how these plants grow and respond to cultural practices and to their environmen ...

, his retirement saw work on a commentary on Vergil's ''Georgics

The ''Georgics'' ( ; ) is a poem by Latin poet Virgil, likely published in 29 BCE. As the name suggests (from the Greek word , ''geōrgika'', i.e. "agricultural (things)") the subject of the poem is agriculture; but far from being an example ...

'', which was published posthumously in 1990. He translated the correspondence of the humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

Desiderius Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' wa ...

for the University of Toronto Press

The University of Toronto Press is a Canadian university press founded in 1901. Although it was founded in 1901, the press did not actually publish any books until 1911.

The press originally printed only examination books and the university calen ...

, and maintained an interest in the nearby Hereford Cathedral

Hereford Cathedral is the cathedral church of the Anglican Diocese of Hereford in Hereford, England.

A place of worship has existed on the site of the present building since the 8th century or earlier. The present building was begun in 1079. S ...

, serving as the chairman of the Friends of the Cathedral from 1979 to 1984. In 1980, the cathedral's parish set up a fund in Mynors's name to acquire a collection of rare books.

On 17 October 1989, Mynors was killed in a road accident outside Hereford

Hereford () is a cathedral city, civil parish and the county town of Herefordshire, England. It lies on the River Wye, approximately east of the border with Wales, south-west of Worcester and north-west of Gloucester. With a population ...

on his way back from a day working on the cathedral's manuscripts. He was buried at St Weonards. Meryl Jancey, the cathedral's Honorary Archivist, later revealed that Mynors had on the same day expressed his delight about his own scholarly work on the death of Bede: "He told me he was glad that he had translated for the ''Oxford Medieval Texts'' the account of Bede's death, and that Bede had not ceased in what he saw as his work for God until the very end."

Contributions to scholarship

Cataloguing manuscripts

Mynors's chief interest lay in palaeography, the study of pre-modern manuscripts. He is credited with unravelling a number of complex manuscript relationships in his catalogues of the Balliol and Durham Cathedral libraries. He had particular interest in the physical state of manuscripts, including examining blots and rulings. For the Balliol archivist Bethany Hamblen, this interest typifies the importance Mynors gave to formal features when evaluating hand-written books.Critical editions

A series of critical editions on Latin authors constitutes the entirety of Mynors's purely classical scholarship. Because of his reluctance toemend

Aprepitant, sold under the brand name Emend among others, is a medication used to prevent chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) and to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). It may be used together with ondansetron and de ...

beyond the transmitted readings, Mynors has been described as a conservative textual critic. This approach is thought to have originated in his tendency to ascribe great historical value to manuscripts and their scribe

A scribe is a person who serves as a professional copyist, especially one who made copies of manuscripts before the invention of automatic printing.

The profession of the scribe, previously widespread across cultures, lost most of its promi ...

s.

The first of his critical editions is of the ''Institutiones'' of Cassiodorus, the first produced since 1679. In the introduction, Mynors offered new insights into the complex manuscript tradition without resolving the fundamental question of how the original text was expanded in later copies. The edition was praised by the reviewer Stephen Gaselee in ''The Classical Review

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

'', who said that it would provide solid foundations for a commentary; writing for the ''Journal of Theological Studies

''The Journal of Theological Studies'' is an academic journal established in 1899 and now published by Oxford University Press in April and October each year. It publishes theological research, scholarship, and interpretation, and hitherto unpubli ...

'', Alexander Souter described it as a "definitive edition" and praised Mynors's classification of the manuscripts.

In 1958, Mynors published an edition of the poems of Catullus. His text followed two recent editions by Moritz Schuster (1949) and Ignazio Cazzaniga (1956), with which he had to compete. Taking a conservative stance on the problems posed by Catullus's text, Mynors did not print any modern emendations unless they corrected obvious scribal errors. Contrary to his conservative instincts, he rejected the traditional archaising orthography

An orthography is a set of conventions for writing a language, including norms of spelling, hyphenation, capitalization, word breaks, emphasis, and punctuation.

Most transnational languages in the modern period have a writing system, and mos ...

of the manuscripts in favour of normalised Latin spelling. This intervention was termed by the philologist Revilo Oliver as "the victory of common sense" in Catullan criticism. For the reviewer Philip Levine, Mynors's edition sets itself apart from previous texts by its scrutiny of a "large bulk" of unexamined manuscripts. Writing in 2000, the Latinist Stephen Harrison criticised Mynors's text for the "omission of many important conjectures from the text", while lauding it for its handling of the manuscript tradition.

His edition of Pliny's ''Epistulae'' employed a similar method but aimed to be an intermediate step rather than an overhaul of the text. Mynors's edition of the complete works of Vergil revamped the text constructed by F. A. Hirtzel in 1900 which had become outdated. He enlarged the manuscript base by drawing on 13 minor witnesses

In law, a witness is someone who has knowledge about a matter, whether they have sensed it or are testifying on another witnesses' behalf. In law a witness is someone who, either voluntarily or under compulsion, provides testimonial evidence, e ...

from the ninth century and added an index of personal names. Its judgement of these minor manuscripts, in particular, is described by the Latinist W. S. Maguinness as the edition's strength. Given the incomplete state of the ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan_War#Sack_of_Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to ...

'', Vergil's epic poem on the wanderings of Aeneas

In Greco-Roman mythology, Aeneas (, ; from ) was a Trojan hero, the son of the Trojan prince Anchises and the Greek goddess Aphrodite (equivalent to the Roman Venus). His father was a first cousin of King Priam of Troy (both being grandsons ...

, Mynors departed from his cautious editorial stance by printing a small number of modern conjectures.

Mynors established a new text of Bede's ''Ecclesiastical History'' for the edition he published together with the historian Bertram Colgrave. His edition of this text followed that of Charles Plummer

Charles Plummer, FBA (1851–1927) was an English historian and cleric, best known as the editor of Sir John Fortescue's ''The Governance of England'', and for coining the term "bastard feudalism". He was the fifth son of Matthew Plummer of St ...

published in 1896. Collation

Collation is the assembly of written information into a standard order. Many systems of collation are based on numerical order or alphabetical order, or extensions and combinations thereof. Collation is a fundamental element of most office filin ...

of the Saint Petersburg Bede

The Saint Petersburg Bede (Saint Petersburg, National Library of Russia, lat. Q. v. I. 18), formerly known as the Leningrad Bede, is an Anglo-Saxon illuminated manuscript, a near-contemporary version of Bede's 8th century history, the '' His ...

, an 8th-century manuscript unknown to Plummer, allowed Mynors to construct a new version of the M tradition. Although he did not append a detailed critical apparatus

A critical apparatus ( la, apparatus criticus) in textual criticism of primary source material, is an organized system of notations to represent, in a single text, the complex history of that text in a concise form useful to diligent readers and ...

and exegetical notes, his analysis of the textual history was praised by the Church historian Gerald Bonner

Gerald Bonner (18 June 1926 – 22 May 2013) was a conservative Anglican Early Church historian and scholar of religion, who lectured at the Department of Theology of Durham University from 1964 to 1988. He was also an author and an internati ...

as "lucid" and "excellently done". Mynors himself considered the edition superficial and felt that its publication had been premature. Winterbottom voices a similar opinion, writing that the text "hardly differ dfrom Plummer's".

Commentary on the ''Georgics''

His scholarly legacy was enhanced by his posthumously published commentary on Vergil's ''Georgics''. A comprehensive guide to Vergil'sdidactic

Didacticism is a philosophy that emphasizes instructional and informative qualities in literature, art, and design. In art, design, architecture, and landscape, didacticism is an emerging conceptual approach that is driven by the urgent need to ...

poem on agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to ...

, the commentary has been lauded for its meticulous attention to technical detail and for Mynors's profound knowledge of agricultural practice. In spite of its accomplishments, the classicist Patricia Johnston has noted that the commentary fails to engage seriously with contemporary scholarship on the text, such as the tension between optimistic and pessimistic readings. In this regard, Mynors's last work reflects his lifelong scepticism towards literary criticism of any persuasion.

Legacy

During his career, Mynors gained a reputation as "one of the leading classical scholars of his generation". He drew praise from the scholarly community for his textual work. The Latinist Harold Gotoff states that he was an "extraordinary scholar", while Winterbottom describes his critical editions as "distinguished". His Oxford editions of the poets Catullus and Vergil in particular are singled out by Gotoff as "excellent"; they still serve as the standard editions of their texts in the early 21st century.Honours

Mynors was elected aFellow of the British Academy

Fellowship of the British Academy (FBA) is an award granted by the British Academy to leading academics for their distinction in the humanities and social sciences. The categories are:

# Fellows – scholars resident in the United Kingdom

# C ...

in 1944 and made a Knight Bachelor

The title of Knight Bachelor is the basic rank granted to a man who has been knighted by the monarch but not inducted as a member of one of the organised orders of chivalry; it is a part of the British honours system. Knights Bachelor are the ...

in 1963. He was granted honorary fellowships by Balliol College, Oxford (1963), Pembroke College, Cambridge (1965), and Corpus Christi College, Oxford (1970). The Warburg Institute

The Warburg Institute is a research institution associated with the University of London in central London, England. A member of the School of Advanced Study, its focus is the study of cultural history and the role of images in culture – cros ...

honoured him in the same way. Mynors was also an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and ...

, the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

, and the Istituto Nazionale di Studi Romani ( it). He held honorary degrees from the universities of Cambridge, Durham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

*County Durham, an English county

* Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in N ...

, Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, Sheffield

Sheffield is a city status in the United Kingdom, city in South Yorkshire, England, whose name derives from the River Sheaf which runs through it. The city serves as the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is Historic counties o ...

, and Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

. In 1983, on his 80th birthday, Mynors's service to the study of Latin texts was honoured by the publication of ''Texts and Transmission: A Survey of the Latin Classics'', edited by the Oxford Latinist L. D. Reynolds. In 2020, an exhibition was held at Balliol to commemorate his scholarship on the college library.

Publications

The following books were authored by Mynors: * * * * * * * * * *Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Mynors, Roger 1903 births 1989 deaths British identical twins People educated at Eton College People educated at Summer Fields School Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford Members of the University of Cambridge faculty of classics Fellows of Balliol College, Oxford Knights Bachelor British classical scholars Anglo-Saxon studies scholars Road incident deaths in England Corpus Christi Professors of Latin Scholars of Latin literature Fellows of the British Academy Codicologists English twins British medievalists English palaeographers Burials in Herefordshire Latin–English translators Kennedy Professors of Latin Presidents of the Classical Association